It’s July 2015. I just completed my first two weeks of college football training. Coach K .* was my defensive coordinator.

“Raines, I’m very impressed with your work this summer. The strength coaches have given me a glowing report about you. We only allowed 110 players in preseason camp because of the NCAA rules. So we filled the remaining spots with seniors. We were planning to redshirt this year so it was more sensible to allow older players to get the reps.

My mind was racing. I was angry, disappointed, embarrassed and annoyed.

I was screwed

It’s tough to be an 18-year old freshman on a football team in college. It’s tough to be an 18-year old walk-on for a college team. You are trying to fit in. You want to be like the other guys. You don’t feel as if you’re one of the boys because you don’t have a scholarship. Even though you’re part of the same team as your teammates, you feel like an outcast.

There is one thing that can help you to achieve equality: Practice.

Everyone competes the same drills and pads whether they have athletic money or not. For walk-ons it is their only chance to prove the coaches wrong.

But I didn’t get to participate in the preseason camp because I was not deemed to be one of the top 110 players.

And I was a little pissed.

College coaches are very good at spotting talent. It’s not surprising that the coaches’ livelihoods are dependent on how well they can train a group 18- to 22-year old kids on a Saturday. They choose the players who are most likely to succeed on the field. Coaches are better at assessing their players than players themselves.

Do not get me wrong. I was an excellent high school footballer. All-regional, played tight end and defensive line, captain of the team. But, because of my league’s high level of competition, I believed I was a really good.

A high schooler’s stats are impressive: 160 yards receiving, two touchdowns, an interception, 10 tackles and a blocked punt. But these stats don’t matter much when the majority of offensive linemen weigh less than 200 lbs.

The talent level of private school football players in Georgia isn’t very high.

My high school pedigree made me believe I was very, very good. However, my perception was distorted by the league I played in. I didn’t realize the difference in skill between my new opponents at Mercer University, and those I played against at Tiftarea Academy.

Never once did I think that these men, who have been coaching college football for over 20 years, are very good at evaluating players. I could be objectively worse than 110 of the other players on my team.

“They really want ________ over me?” was all I could think. _________??? Seriously??”

I did not know.

And _______ could be a variety of people depending on the time. )

When I returned to the team a few months later for practice, I had set myself two goals.

1 – Dominate those I consider to be inferior

2) Play against our best players whenever possible

Lucky for me, there were plenty of opportunities to do both. As a redshirted athlete, I had plenty of opportunities to compete against our starters on the scout squad.

You can probably guess that I was smoked quite a bit. As a 230 pound freshman defensive lineman, I was smoked on board drills. In high school I never had to worry much about my arsenal of pass-rush moves. But in 1 on 1, with the offensive lines, I was embarrassed.

Ironically, I didn’t realize that I was a sucka. I was ignorant.

I knew I was losing a lot of reps but figured it was part of the learning process as a freshmen coming from a small school. It didn’t help either that I missed preseason training.

Every week I get my a$$ kicked in practice.

It’s funny that after getting your a$$ kicked for a while, you start to get better at not having your s**t kicked. You improve and learn.

In order to compensate for the fact that I was not as big as my opponent, I began firing the ball faster. I stopped blindly running towards my opponent’s chest, a strategy which works against smaller high school offensive linesmen but not against men 6’5″ and 300 pounds. Instead, I began using my hands to defend myself.

At the end of my debut season, I was still not good. As a defensive end weighing 230 pounds, I was still too small. I had to become stronger. I needed to improve my pass rush moves.

I did win a few reps, but not all of them. But I also understood why I was losing reps. I was able to see where I could improve.

But I was ignorant of the suck. To me, the suck was not apparent. I just saw myself as an ongoing project.

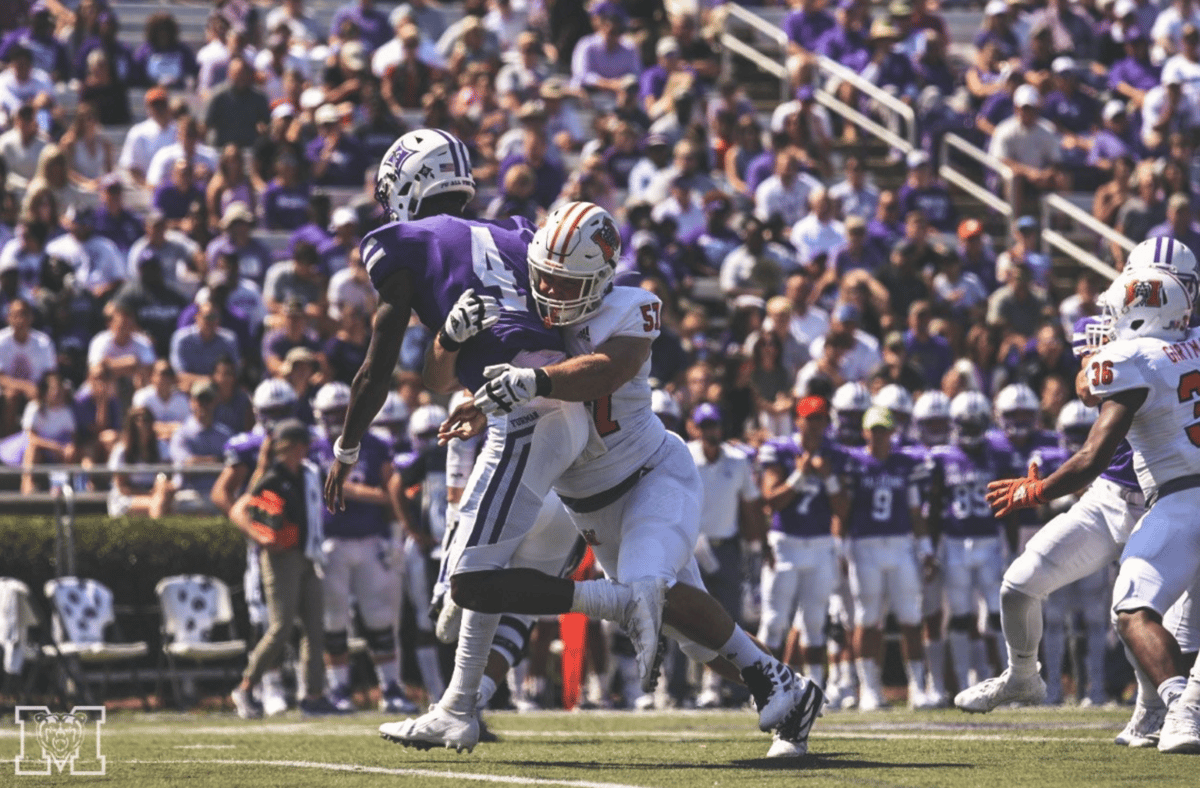

I did not have a transformation overnight. As a redshirt freshmen, I did not shock everyone by winning a starting position. In my second year, I did a few special teams reps. In my third season, I earned a full scholarship and was playing 20+ snaps a game. By the time I reached my 5th year senior year, I had become our defensive end starter and team captain.

Between the ages of 18 and 22, my suckiness stopped.

Thank God For Ignorance

If I had known at the beginning of my football career 1) how difficult football is, 2) how big the gap between my skill level and that of my teammates, and 3) how good coaches are in assessing talent, I would probably have quit the season after.

But I was ignorant. I believed I was better than what I was. I had unrealistic expectations about my ability to progress, and I saw being rejected for preseason as an antagonistic, motivational spark, instead of a rational choice by my coaches.

Ignorance is often criticized, but if you use it correctly, ignorance can give you the time needed to make a difference between failing and succeeding. You would never begin a new venture if you knew the risks involved and the low chances of success. If your ignorance keeps you going, you might succeed, no matter what it is.

Ignorance plus discipline is a cheating code.

Today, I am still a bit ignorant of a lot.

About a year and a half ago, I found out that some writers were earning a lot of money. I thought, “Huh. It looks like fun. I should try it. You can make money if you build an audience.

I never thought, “damn, it will take forever to get an audience.” Will I run out ideas? How many writers fail? “

The bell curve meme: I am the right and left side.

If you write for long enough, it seems that “just writing stuff” is effective. It’s like how “just practicing stuff” on the football pitch works if you do it long enough.

If you do enough things, it will work.