The first of two posts that I will be writing about my thoughts on money. The second half will be released on Thursday. I hope you like it.

The Value of Time principle is an important finance concept that tells us the amount of change in value between two dates, given an annual return.

Using the Time Value Money, we can calculate that $10,000 spent for 40 years with an average return of 9% per year would result in $314,094. Alternatively, the current value of $314.094 in 40 year’s time is $10,000.

What amount do you have to invest right now if you are aiming for $1,000,000 over 40 years at 9% return? We can find the answer by working backwards.

( If you haven’t noticed, I’ve been doing my corporate finance homework to the hilt.

In every field of finance, the time value of money is important. Car loans and mortgages are amortized. The 401k plan will estimate the amount of contributions you need to make in order to reach your retirement goals. Investors discount future cash flow of companies to estimate fair value, while companies discount future cash flow of projects to determine whether they are worth undertaking.

Most mainstream financial advice is based on the time value of money: Spend less now and you will have exponentially more in the future.

This has resulted in a flood of advice which deifies stinginess and vilifies frivolous spending.

“Don’t Buy Your Coffee From Starbucks!” “Don’t buy your coffee from Starbucks!” yells a swarm of Dave Ramsey disciples. “This $50 per month is going to cost you $221 575 over 40 years!” “

“Pour all your non-essential dollars into your index fund!” The FIRE movement is loudly supported by its most vocal supporters. ” Each dollar you spend now will only delay your retirement.

Over time, advice that was well-intentioned such as ” Make less money than you spend ” has become ” Do not spend anything or else.” When you repeat this message enough times, people start to believe it.

Like most young people I grew up thinking of money as a scarce resource that was to be saved and treasured. You know what to do: Save every penny, don’t spend too much on anything. Venmo everyone in your Uber. Every week, obsess over your bank account balance.

I was being irrational in my worry about money. In college, I had a full-scholarship and was an upper middle class student. As a 22-year old college graduate, I was confident that I could land a high-paying job.

When frugality in the formative years is presented as the only important value for personal finance, you will tend to conform.

After college, I carried this mindset into my first job. You’d better max out your 401K and be careful with weekend spending. This is what every 23-year old thinks when they start their first job.

If you’ve been following me for a little while, you already know what happens. This is a story I have told a thousand times.

I made a lot of money trading stocks during COVID and then lost HALF of it but I still had enough money to just quit working for a year so I lived out of a backpack in Europe and South America for ONE YEAR.

I have written about this story in a number of blog posts and told the tale on more than a dozen podcasts. We are here today, having made money, lost money, traveled, and started writing. What I haven’t talked about is how this moment changed my perception of money.

It is only when you are no longer frugal, that you will realize the dangers of pure frugality.

The majority of people do not reach this stage until they retire, but I was fortunate enough to experience it briefly at the age of 23. Today, I will let you in on an insider’s secret.

When money is no object, what do you do?

We build our careers around the idea that we should acquire as much capital as we can. But when you have acquired all of your capital and are considering what to do next you will realize an important fact:

Money is not something you can eat, breathe, or have sex. Money can’t entertain on its own. Money can’t make anyone laugh, smile, or cry. Money can’t bring you fond memories and will not ignite your soul. Money cannot form a lasting relationship (many people have tried but it never reciprocates the love they give).

Money is worthless in itself.

Money can be exchanged, however, for something that is infinitely valuable: Experiences.

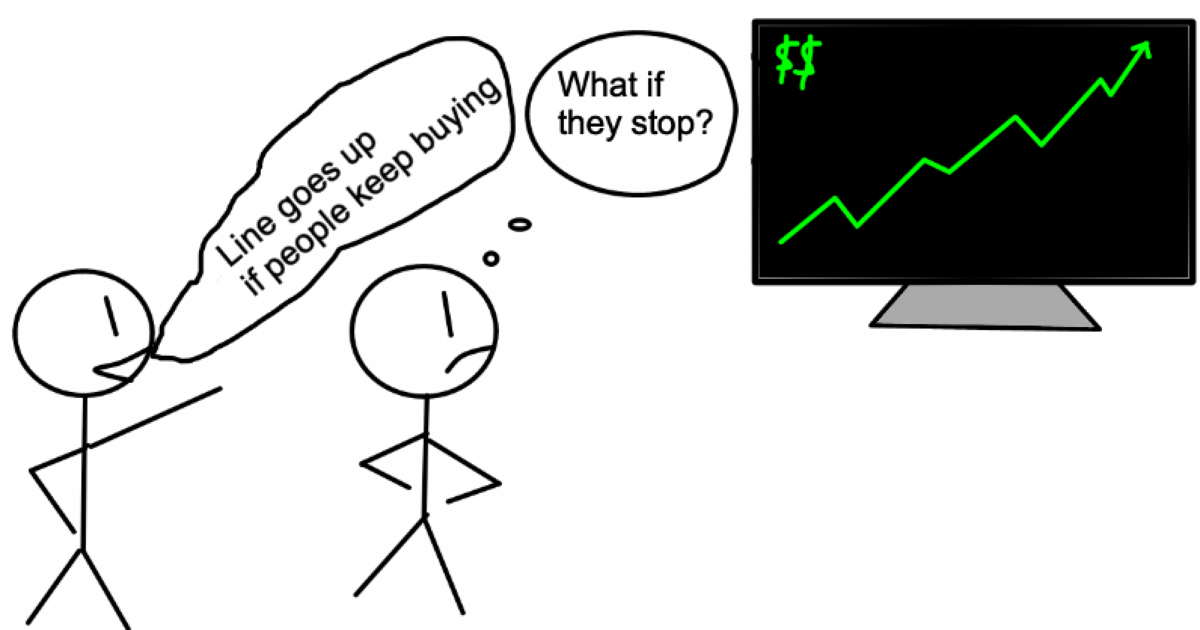

If investing were a simple quantitative game where dollars and lines went up and the goal was to have the highest number, then every penny extra should be thrown into the stock markets. $221,575 sounds like a lot of money. Of course, you’d choose it over $50 worth of coffee each month.

But investing is not just a game of dollars compounding and lines rising. Investing is just one part of our chaotic and confusing lives.

According to The Time Value of Money, delaying spending increases the value of your investment portfolio over time. If we had an unlimited amount of time, the story would end here. Spend as little as possible now to accumulate as much as you can at a future date.

We don’t have infinite time. You need to flip the equation in order to get the whole picture about the relationship between time and money. The Time Value Of Money shows how the value of an asset will change over time based on an annual return. But the Money Value of Time tells us how long we have to spend that money in order to get an experience. In the first case, money tends increase with time. However, in the second case time tends decrease.

Money has only one purpose, and that is to be exchanged in exchange for experiences. It makes no difference whether you plan to exchange the dollars now or at a later date. The value of money increases over time but your ability to use that money to buy experiences also decreases.

Extreme frugality can be dangerous because it causes you to sacrifice many experiences in the early years of your life in order to try and cram as much in during your retirement.

Opportunities are different over time. You won’t have the same experiences at 55 that you had at 25, and even if you do, you will not enjoy them as much. You will miss out on some of the most life-changing moments if you spend too much time worrying about investing for retirement in your 20s.

People often forget this when thinking about retirement, money, and life in general. The idea that “it can be done later” gives us comfort.

It is as dangerous to spend every dollar on frivolous, cheap thrills as it is to put all your money into index funds. Spending your life avoiding fun can lead to the realization, much too late, of having more money than needed and missing out on some of your greatest opportunities to spend it.

As a young man of 23, I became aware of this inequity and it was a source for anxiety. I felt a constant sense of urgency: “I need to do the fun stuff right now or I won’t get to it.”

My mental problems manifested in the most cliche way: a guy in his 20s, with some extra money, throws caution to wind and embarks on an adventure through Europe. It was cliche. It was also logical.

At 35, I realised that I would not want to travel Europe by train and stay in hostels. This vagabonding life of sharing rooms with strangers would be miserable. But at 24? It was the greatest adventure of all time. Missed a flight? Who cares? Who cares if you get invited to Prague by some guys that you met in Barcelona the night before? You can go along. Do overnight trains allow you to sleep? Why not?

The experience was more important than the cheapness. This same rugged, cheap “fun” was a living nightmare if I did it 25 years later.

It’s funny that I am not the only one who sees money, time and opportunity costs this way.

Bill Perkins, a hedge-fund manager, film producer and professional poker player, is a modern day Renaissance man.

Perkins wrote one of the best finance books in the last decade, Die With Zero .

The thesis of the book is straightforward: spend your money only on experiences you enjoy so that, as suggested by the title, you “die with nothing”. You must accept that you will value different experiences at different times in your life.

Perkins describes in the early chapters of his book how his roommate took a rash decision to travel Europe for three months ( sounds like)

Jason Ruffo was my roommate when I was in my early 20s. He decided to take three months off work to backpack through Europe. The same friend I shared a Manhattan apartment with, a pizza oven-sized one. We both worked as screen clerks and made about $18,000 per year.

Jason had to stop working to make this trip a reality. He would also have to borrow ten thousand dollars from a loan shark, the only person willing to lend him such a large sum of money.

I asked Jason: “Are You Crazy? You’re borrowing money from a shark? “You’ll break your legs!” I was not only concerned about Jason’s safety. Jason’s job would suffer if he went to Europe. The idea of going on a trip like that seemed as alien to me as the moon. I was not going with him.

Jason was determined to go, and he took off for London with Eurail and no schedule. He was both nervous and excited. There was no difference in his income when he returned a few month later. But the pictures and stories he told about his adventures showed that his experience was worth more than his money.

He felt his world expanding as he met young travelers and locals from around the globe. I was so impressed by his stories about the cultures he visited and the connections that he made, I was envious. I also regretted not going.

The feeling of regret grew as time went on. It was too late when I went to Europe at 30. I was too old and too affluent to hang out in youth hostels with 24-year-olds. By the time I reached 30, I had more responsibilities and was older than when I was in my early 20s. This made it harder for me to travel for months.

I had to admit that I was wrong. Jason, like me, knows that he planned his European trip perfectly. Jason says, “I would not enjoy sleeping with 20 other guys in a shabby bunk bed, nor would I enjoy carrying around a 60-pound bag on trains or through the streets.” But, unlike me, Jason actually went on the trip. He has no regrets about the trip, even though he took out a high-interest loan. He tells me, “I feel that whatever I paid was a bargain due to the life experiences that I gained.”

Bill Perkins Die With Zero

As time went on, the regret only increased. It was too late when I went to Europe at 30. I was too old, too snobby and too affluent to hang out in youth hostels with 24-year-olds. By the time I reached 30, I had more responsibilities and was older than when I was in my early 20s. This made it harder for me to travel for months. “

While it’s unsettling to consider that we may be unable to take advantage of some opportunities as we age, the time window in which to experience most things is much shorter than you think. We must act accordingly.

The writer continues:

Our ability to experience different types of experiences changes over our lifetime.

Imagine that your parents brought you to Italy as a child. What did you gain from this expensive trip, other than a love for gelato throughout your life? Consider the opposite extreme: Do you think you will enjoy climbing Rome’s Spanish Steps in your 90s, assuming you are still alive?

To get the best out of time and money, you need to make the right decisions. To increase your overall life satisfaction, you should have each experience in the right age.

Bill Perkins Die With Zero

I don’t think everyone would consider a backpacking tour in Europe to be their dream trip. It would be hell for many people, no matter their age. It’s true that everyone has dreams, whether it’s to travel abroad, live somewhere new in the US or experiment with a career path. But these dream experiences are often put off indefinitely, because “the time is not right.” You “can’t take the risk now.”

Truthfully, it’s never the right time to make a drastic change. Either you decide to take the leap or not. If you wait too long to pursue your dream, the opportunity will pass you by.

The real danger is not that you will run out of cash or fail. You could miss out on countless opportunities in your lifetime because the “risk was too high.” Let’s face it, would it be that difficult to restart if you hit rock bottom?